The Passover and Crucifixion Scenario

— a Revisitation —

By Paul W. Syltie, Ph.D

As a former part of the Worldwide Church of God (WCG) from 1971 to 1995, I was taught to keep the Passover in particlar ways at a particular time, which my wife and I obediently did for many years. Personal research into this matter, as well as other matters of doctrine, were frowned upon; that research was to be reserved for certain experts in Pasadena, California, who purportedly had superior knowledge and authority to dictate to others in the body what to do. As loyal followers of the hierarchy we did not question directives of the researchers at headquarters for many years, but while diligently studying the word of God, and being challenged by others on several topics, understandings that differed from standard WCG doctrines began to take hold.

These understandings developed because they were quite obvious from a reading of the Scriptures, in particular issues relating to the Passover and crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Several things concerning the “approved” version of this most critical time period did not add up. It has become my preferred method of research over the years to focus first on the obvious — the facts that can most easily and irrefutably be proven — and work outward from there to fill in the less obvious matters to complete the picture.

Using this system of scholarship, I will hereafter delineate the time frame of the Passover and Days of Unleavened Bread in the year that Jesus Christ was crucified, ignoring the many scenarios that have been presented over the years and zeroing in on the messages that the word of God delivers. This will not be a difficult task, because the Scriptures are quite clear on this matter … at least the basic framework of it. I will bring in supporting evidence from some extra-Biblical sources as we move along. So, let us begin this exciting adventure.

Let me make one important comment before that adventure begins. The knowledge of the exact crucifixion and resurrection dates of Jesus are not essential for salvation, Nevertheless, it is valuable to understand the drama and truth regarding this most critical event in the history of the world, for without Jesus’ sacrifice for our sins we would all be without hope. Because He did die willingly for our sins, we have an undying hope that carries us through each day as we await the return of our Messiah very soon. We all ought to desire the truth in all things, especially those related to our great God, so this foray into Scripture ought to be an exciting adventure for all of us truth seekers

1. Jesus Kept the Passover At the Time the Torah Prescribed,

Nisan 14 Going Into Nisan 15

It has been common for some researchers of the Passover chronology to presume that Jesus and the disciples kept the Passover a day earlier than the prescribed Nisan 14 time described in the Old Testament. They did this in some instances to try and squeeze “three days and three nights” — 72 hours — between the time of His death and resurrection … but more on that later. The fourteenth day of the first month (Nisan), however, is when this event was to be observed, as the two citations below make clear (ESV).

“Your lamb shall be without blemish, a male a year old. You may take it from the sheep or from the goats, and you shall keep it until the fourteenth day of this month, when the whole assembly of the congregation of Israel shall kill their lamb at twilight …. This day shall be for you a memorial day, and you shall keep it as a feast to the Lord; throughout your generations, as a statute forever, you shall keep it as a feast” (Exodus 12:5-6, 14).

“In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month at twilight [between the two evenings] is the Lord’s Passover” (Leviticus 23:5).

The Hebrew word for “twilight”, translated “even” in the KJV and “evening” in the NKJV in the above two citations, is ereb (Strong 6153), which comes from the Hebrew arab (Strong 6150), meaning to “cover with a texture, to grow dusky at sundown, or be darkened toward evening.” To make clear what time of the day this is referring to, God made a point of clarifying the issue in Leviticus 23:32, when he said, regarding the Day of Atonement, “On the ninth day of the month beginning at evening [ereb], from evening to evening, shall you keep your Sabbath.” The Day of Atonement is to be kept on the tenth day of the seventh month (Leviticus 23:27), so it is obvious that the “evening” which begins the fasting day is at the end of the ninth day, not the beginning of the ninth. Likewise, the evening of the fourteenth day (Leviticus 23:5) is at the end of the fourteenth day, not at the beginning.

Now, we can read in the gospels concerning the last Passover before Christ’s crucifixion. Note that they all say that this was the Passover, not a pre-Passover or some other event.

“Now on the first day of Unleavened Bread the disciples came to Jesus, saying, ‘Where will you have us prepare for you to eat the Passover?’ He said, ‘Go into the city to a certain man and say to him, “The Teacher says, My time is at hand. I will keep the Passover at your house with My disciples”’ And the disciples did as Jesus had directed them, and they prepared the Passover” (Matthew 26:17-19).

Note that the above citation indicates it was the “first day of Unleavened Bread”. The Hebrews considered the Passover day (Nisan 14) as being part of the other seven days of Unleavened Bread, since the leaven was removed that fourteenth day. Note Luke 22:7 where the text says, “Then came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the Passover lamb had to be sacrificed.” John 13:1 lumps the Passover with the days of Unleavened Bread: “Now before the Feast of the Passover ….” Also, Mark 14:12 states, “And on the first day of Unleavened Bread, when they sacrificed the Passover lamb ….”

“And on the first day of Unleavened Bread, when they sacrificed the Passover lamb, His disciples said to Him, ‘Where will you have us go and prepare for you to eat the Passover?’ And He sent two of His disciples and said to them, ‘… The Teacher says, Where is My guest room, where I may eat the Passover with My disciples?’ … And the disciples set out and went to the city and found it just as He had told them, and they prepared the Passover” (Mark 14:`12-16).

“Then came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the Passover lamb had to be sacrificed. So Jesus sent Peter and John, saying, ‘Go and prepare the Passover for us, that we may eat it.’ ‘… and tell the master of the house, “The Teacher says to you, Where is the guest room, where I may eat the Passover with My disciples?” And he will show you a large upper room furnished; prepare it there.’ And they went and found it just as He had told them, and they prepared the Passover” (Luke 22:7-13).

John speaks of the “Feast of the Passover” in John 13:1 by saying, “Now before the Feast of the Passover,” which seems to say that this observance (John 13:2) actually preceeded the true Passover. However, the word before in verse one is the Greek pro (Strong 4253), which is a primary preposition meaning “in front of.” The Passover is indeed “in front of” the other seven days of Unleavened Bread, so there is no conflict here with the other three gospels.

Let us look more closely at John 13:1 and see what other translations and commentators have to say about this scripture. The Moffatt translation for John 13:1 is as follows:

“Now before the Passover festival Jesus knew that the time had come for Him to pass from this world to the Father. He had loved His own in this world and He loved them to the end.”

James Moffatt reveals the essence of the statement as saying that Jesus knew before the Passover that He would be giving His life. Moreover, Norval Geldenhuys stated,

“If, however, we take the expression ‘before the feast’ along with ‘knowing’, the verse immediately reads more naturally, for then we may translate it as follows: ‘Knowing (already) before the Passover that His hour had come to depart out of this world unto the Father, Jesus, He who loved His own in this world, loved them unto the end (or “to the uttermost”)’. When thus translated, this verse gives beautiful sense as a prologue or a summarizing title to what follows in chapters 13 to 18 [of John]. Accordingly, this translation gives a deep and glorious meaning to the words of John and is perfectly clear and intelligible” (Commentary on the Gospel of Luke: the English Text, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1971, pages 657-658).

Other non-gospel references also indicate that Jesus and the disciples kept the true Passover. Note the symbols of bread and wine indicated by Paul in I Corinthians 11:23-26, as one example.

Quite a number of commentators on the Passover observance of Christ and the disciples attempt to place this observance a day before the fourteenth of Nisan, opting for the thirteenth, arguing that the Calendar Court of the Hebrews that year ruled that the first day of the sacred year could not be accurately determined enough to allow the rulers to be dogmatic on one day; thus, they ostensibly allowed two possibilities for the first day of the sacred new year, and for the Passover observance. One such reference is authored by Vernon Jones and B.L. Cocherell (Which Day Is the Christian Passover, Answers Research and Education, San Jose, California, 1991). However, Jones’ and Cocherell’s thesis is directly contradicted by the eminent Jewish-turned-Christian scholar Alfred Edersheim, who had the following to say.

“At the outset we may dismiss, as unworthy of serious discussion, the theory, either that our Lord had observed the Paschal Supper at another than the regular time for it, or that St. John meant to intimate that he had partaken of it on the 13th instead of the 14th of Nisan. To such violent hypotheses, which are wholly uncalled for, there is this one conclusive answer, that, except on the evening of the 14th of Nisan, no Paschal lamb could have been offered in the Temple, and therefore no Pascal Supper celebrated in Jerusalem” (Alfred Edersheim, The Temple, Its Ministry and Services, Hendrickson Publishers, Inc., Peabody, Massachusetts, 1994, page 193; published first in London, England, in 1874). [Emphasis mine]

To add weight to Alfred Edersheim’s belief that the last Passover of Jesus and the disciples before His crucifixion occurred at the end of Nisan 14, going into Nisan 15, his Appendix on pages 311 to 318 of The Temple is included at the end of this paper for those who wish to study this topic in further depth.

The argument that John 18:28 proves that the Jews had not yet kept the Passover, proving that Jesus and the disciples had kept an “early” Passover or seder meal, is now examined. First, let us read the verse.

“Then they led Jesus from the house of Caiaphas to the governor’s headquarters [the Praetorium]. It was early morning. They themselves did not enter the governor’s headquarters, so that they would not be defiled, but could eat the Passover.”

First of all, the last sentence is grammatically complete and makes sense if a period is placed after “defiled” in the quote above. The clause, “… but could eat the Passover,” stands alone and adds further information to the preceeding sentence, just as John meant it to. The word “but” comes from the Greek word alla, a rarely used word in the New Testament, meaning “therefore, other things, contrariwise, but properly, nevertheless.” John is adding a thought that helps explain the preceding statement. If John was wanting to add a statement that the Jews were yet going to eat the Passover, he would have used the common Greek word kai, which is a conjunction meaning “and”.

Let us now examine the words “could eat” in John 18:28. In Greek this word is phago. John did not use the future tense here, which he would have used had he meant to covey that the Jews were yet to eat the Passover. According to Spiros Zodhiates in Complete Word Study New Testament (AMG Publishers, Chattanooga, Tennessee, 1991), John used the aorist subjunctive active tense here, which means a “… simple, undefined action …. the verb does not have any temporal significance. In other words, it refers only to the reality of an event or action, not to the time when it took place.”

Thus, the phrase “but could eat the Passover” does not say the Passover was a future event, since “could eat” (alla) does not indicate time of occurrence. It can indicate a future event, or it can indicate a past event as in Matthew 15:32; Mark 6:36, and Mark 8:1-2. It makes perfect sence that John is saying the Jewish priests were ritually clean from their cleansing ceremonies, they had properly observed the Passover, and now, since they would be officiating and eating of all the sacrifices of the feast of Unleavened Bread, they would not dare to enter the praetorium and defile themselves.

It is also plausible that “eat the Passover” refers to the coming six days of the feast of Unleavened Bread, when the priests would be eating of the sacrifices. Since the “Passover” in John’s account can refer to the entire eight-day feast, then it is very logical to presume this is what John meant. In any case, there is no proof in John 18:28 that the Jewish priests had yet to keep the Passover, for they already had … at the same time that Jesus and the disciples had, the evening of Nisan 14 going into Nisan 15.

Edersheim (1874) adds the following regarding the priests being defiled in John 18:28. This information is extracted from the Appendix at the end of this paper. “When St. John mentions (John 18:28) that the accusers of Jesus went not into Pilate’s judgment-hall ‘lest they should be defiled; but that they might eat the Passover,’ he could not have referred to their eating the Paschal Supper. For the defilement thus incurred would only have lasted to the evening of that day, whereas the Paschal Supper was eaten after the evening had commenced, so that the defilement of Pilate’s judgment-hall in the morning would in no way have interfered with their eating the Paschal Lamb. But it would have interfered with their either offering or partaking of the Chagigah on the 15th Nisan.”

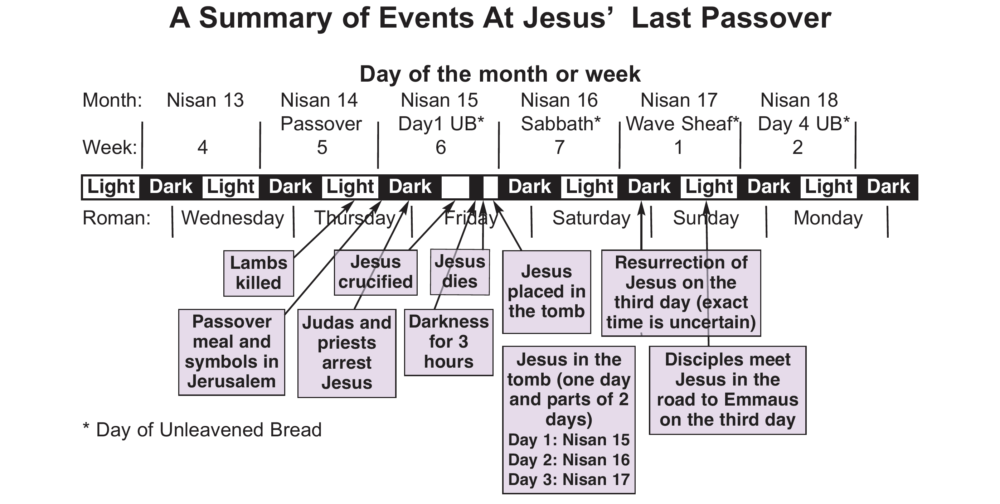

2. Jesus Was Crucified on a Friday, and Raised After the Sabbath …

the Third Day

Crucified a Day Before the Sabbat

The accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion state plainly that the next day was a “preparation day”. Note the following gospel verses.

“The next day [after the crucifixion], that is, after the day of Preparation, the chief priests and the Pharisees gathered before Pilate …” (Matthew 27:62).

“And when evening had come, since it was the day of Preparation, that is, the day before the Sabbath, Joseph of Arimathea, a respected member of the council, who was also himself looking for the kingdom of God, took courage and went to Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus” (Mark 15:42-43).

“It was the day of Preparation, and the Sabbath was beginning. The women who had come with him from Galilee followed and saw the tomb and how His body was laid” (Luke 23:54-55).

“Now it was the day of Preparation [during] the Passover [period of eight days; see the previous section]. It was about the sixth hour. He said to the Jews, ‘Behold your King!’ They cried out ‘Away with Him, away with Him, crucify Him!’” (John 19:14-15).

“Since it was the day of Preparation, and so that the bodies would not remain on the cross [stauros in Greek, or “stake”] on the Sabbath (for that Sabbath was a high day), the Jews asked Pilate that their legs might be broken, and that they might be taken away” (John 19:31).

“So because of the Jewish day of Preparation, since the tomb was close at hand, they laid Jesus there” (John 19:42).

The phrase “day of Preparation” is use only in reference to the weekly Sabbath day, not to annual feast days like the first and last days of Unleavened Bread. In Mark 15:42 the Sabbath is mentioned in conjunction with day of Preparation; it is Strong 4315, prosabbaton, or a “fore-sabbath, i.e., the Sabbath eve, or day before the [weekly] sabbath.” In Luke 23:54 and John 19:31 the word for Sabbath, which followed the day of Preparation, is sabbaton (Strong 4521), “the Sabbath, or day of weekly repose from secular avocations.” The Greek word for “preparation” in all of these verses is paraskeue (Strong 3904), meaning “readiness”. Thus, all of these references to the Preparation for the Sabbath refer to the weekly Sabbath, which begins at sunset on Friday evening, and does not refer to any preparations for an annual Holy Day such as the first day of Unleavened Bread.

Another proof that this Preparation day on which the crucifixion took place was a Friday can be found in Luke 23:56. The women who had accompanied Joseph of Arimathea from Galilee prepared spices and ointments to treat Jesus’ body in the tomb, once they had opportunity, but there was no time after His burial in Joseph’s tomb to do so. So, they were forced to wait until after the Sabbath to return to the tomb and treat His body (Luke 24:1), but “On the Sabbath they rested according to the commandment” (Luke 23:56).

We understand that the commandment for keeping the weekly Sabbath specifies that no work is to be done:

“Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labor, and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, you, or your son, or your daughter, your male servant, or your female servant, or your livestock, or the sojourner who is within your gates” (Exodus 20:8-10).

Leviticus 23:3 calls this desisting from work “a Sabbath of solemn rest”, but the command for the other Holy Days is to “not do any ordinary work” (Leviticus 23:7, 8, 21, 25, 31, 35, 36), with the exception of the Feast of Trumpets which was to be a day of “solemn rest” (Leviticus 23:34), and the Day of Atonement, which was also to be a day of “solemn rest” and “affliction” (Leviticus 23:32). Each of these festival days were to be a “holy convocation” as well.

The restrictions for the annual Holy Days was not as stringent as for the weekly Sabbath, with the exception of the Day of Atonement. Food preparation and certain other tasks could be performed on an annual Holy Day that were not allowed on the weekly Sabbath (Exodus 12:16, etc.).

The Third Day … Three Days and Three Nights

Let us examine the issue of the time Jesus was in the tomb of Joseph. There are eighteen separate references in Scripture that Jesus or His disciples spoke of the length of time from His death to His resurrection. These references can be grouped as follows:

(a) Five times as “in” or “within three days” (Matthew 26:61; 27:40; Mark 14:58; 15:29; John 2:19).

(b) Two times as “after three days” (Matthew 27:63; Mark 8:31).

(c) Eleven times as on “the third day” (Matthew 16:21; 17:23; 20:18-19; 27:63-64; Mark 9:31; 10:34; Luke 9:22; 13:32; 18:33; 24:7; Acts 10:39-40).

(d) One time as “three days and three nights” (Matthew 12:38-40).

It is well understood that, in the Hebrew reckoning of time, any part of a day is considered a “day” (Arthus Custance, The resurrection of Jesus Christ, Discovery Paper No. 46, Brookville, 1971, pages 8-11 at www.custance.org/library/Volume 5/Part_VIII/Chapter2.html). As Dr. Custance stated,

“The principle which governed their [the Hebrews’] thinking in such matters has been rather clearly set forth in some of their own commentaries on the Scriptures. It is this: that any part of a whole period of time may be counted as though it were the whole. A part of a day may be counted as a whole day, a part of a year as a whole year. Furthermore, a part of a day or a part of a night may be counted as a whole “night and day.” I suspect that in the Lord’s parable of the man who paid his labourers for a whole day, whether they had worked for a whole day or not (Matthew 20:1-16), is really a reflection of this principle. Thus, in the Babylonian Talmud, the Third Tractate of the Mishnah (which is designated ‘B. Pesachim’) it is stated: ‘The portion of a day is as the whole of it.’” [Emphasis mine]

Examples of this reckoning can be found in the following episodes. The Hebrews used inclusive reckoning in determining days; any part of a day was termed a “day”.

(a) Noah and the Flood. Genesis 7:4: “For in seven days I will send rain on the earth forty days and forty nights ….” Verse 10 states “And after seven days the waters of the flood came upon the earth,” or literally “On the seventh of the days,” or “On the seventh day.”

(b) Queen Esther and the fast. Esther 4:16: “Go, gather all the Jews to be found in Susa, and hold a fast on my behalf, and do not eat or drink for three days, day or night.” Yet, on the third day we find Esther standing in her royal apparel in the inner court (Esther 5:1); she obviously would be partaking of the banquet she had prepared for the king (Esther 5:4) on that third day, less than 72 hours after the fast began.

(c) King David and the Egyptian. In I Samuel 30:10-13 we read of an Egyptian servant telling David that he had not eaten or drank for three days and nights (verse 12). The context reveals that the servant was telling David this on the third day, not at the end of 72 hours since he had ceased eating and drinking.

(d) The four days of Cornelius. In Acts 10, the centurion named Cornelius saw a vision at 3:00 p.m. (verse 3), and was instructed to send men to Joppa and call for Peter. The next day these men reached Peter (verses 8-9). The day after that, the messengers and Peter and others returned from Joppa to visit Cornelius (verse 23), and the day after that they arrived at Caesarea (verse 24). Three days elapsed since the messengers of Cornelius were sent to fetch Peter. However, Cornelius told Peter, “… four days ago I was in my house praying at this hour, at three in the afternoon …” (verse 30). Three days had elapsed, yet Cornelius declared it was four days earlier that he had seen the vision. It is obvious that Cornelius was referring to two full days plus parts of two days, totaling four days in Hebrew reckoning.

It is now apparent that “three days and three nights in the heart of the earth” is an idiom peculiar to the Hebrew language at the time it was written by John in the First Century A.D. We in the modern Western World, with our precise scientific understandings, may find this idiom unfamiliar and rather hard to comprehend.

E. W. Bullinger makes the case clear regarding the “three days and three nights” of Luke 11:29-30 and Matthew12:40. He states the following:

“From all this it is perfectly clear that nothing is to be gained by forcing the one passage (Matthew 12:40) to have the literal meaning, in the face of all these other passages, which distinctly state that the Lord died and was buried the day before the Sabbath and rose the day after it, v. 12., the first day of the week. These many statements are literal and are history: but the one passage [Matthew 12:40] is an idiom which means any part of ‘three days and three nights.’ The one complete day and night (24 hours) and the parts of two nights (36 hours in all) fully satisfy both the idiom and history” (Figures of Speech Used in the Bible, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1968, pages 846-847).

Another source commenting on the three days and three nights issue agrees with Bullinger. R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer, Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke in The Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (Moody Publishers, Chicago, Illinois, 2003, pages 478-479) state that the “three days and three nights” in I Samuel 30:12 “is a stereotyped formula which applies when any part of three days is involved, not an affirmation that seventy-two hours have expired (cf. our Lord’s three days and three nights).”

How are we to view the “heart of the earth” phrase attached to the three days and three nights” in Matthew 12:40? The word “heart” is the Greek kardia (Strong 2588), “the heart, and by an easy transition the man’s entire mental and moral activity, both the rational and the emotional elements; also, the hidden springs of the personal life; it can also mean the middle of something.” “Earth” in this verse is the Greek ge (Strong 1093), meaning “the solid part of the whole of the globe (including the occupants in each application).”

E.W. Bullinger in Figures of Speech Used in the Bible, page 412, states that in Matthew 12:40 the word “heart” is used pleonastically by Metonymy for “the midst”, when it does not mean literally the precise middle point. Thus, this verse literally means “in the midst of the earth”, i.e. in Joseph’s tomb.

To further understand why Jesus told the Pharisees that only the sign of his Messiahship would be the sign of Jonah being in the belly of the great fish for three days and three nights (Matthew 12:40) — which we now know means parts of two days plus one whole day — we need to read Luke 11:29-30, 32, which says,

“When the crowds were increasing, He began to say, ‘This generation is an evil generation. It seeks for a sign, but no sign will be given to it except the sign of Jonah. For as Jonah became a sign to the people of Nineveh, so will the Son of Man be to this generation …. The men of Nineveh will rise up in judgement with this generation and condemn it, for they repented at the preaching of Jonah, and behold something greater than Jonah is here.” (See also Matthew 12:41.)

The analogy of Jonah’s preaching of repentance to Nineveh and Jesus’ preaching of repentance and the Kingdom of God in Israel is superb. However, unlike the Ninevites, who repented and prevented the immediate destruction of that city and nation (Jonah 3:6-10), the Pharisees, Sadducees, priests, lawyers, scribes, and others of the intelligentsia of Israel in Jesus’ time refused to repent of their sins, and these were routinely castigated by Jesus, as in Matthew 23.

The parallels between Jonah and Jesus probably run much deeper yet than this. Most likely Jonah was dead inside the great fish the three days after it swallowed him, until “… the Lord spoke to the fish, and it vomited Jonah out upon the dry land” (Jonah 2:10). As Jesus was dead after the crucifixion and buried within a rock tomb for three days, so was Jonah most likely dead within the fish for three days … protected from decomposing but dead nonetheless. Scripture does not say whether he was dead or not, but it is a small thing for God to raise a dead person back to life, as He did for Lazarus (John 11:43), for the saints around Jerusalem at Christ’s death (Matthew 27:52-532), and of course for Jesus Himself.

The Clear Evidence of

Luke 23 and 24

Portions of Luke 23 and 24 have already been touched upon in this paper, but some verses will be repeated here that reveal with absolute assurance that the crucifixion was on the sixth day of the week. Notice first Luke 23:52-56.

“This man [Joseph of Arimathea] went to Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus. Then he took it down, wrapped it in linen, and laid it in a tomb that was hewn out of the rock, where no one had ever lain before. That day was the Preparation, and the Sabbath drew near. And the women who had come with Him from Galilee followed after, and they observed the tomb and how His body was laid. Then they returned and prepared spices and fragrant oils. And they rested on the Sabbath according to the commandment.”

Notice some salient points in this quote above. The Preparation Day here was Friday, before sunset, as the weekly Sabbath was nearing. How do we know? Because the very next verse (Luke 24:1) states, “Now on the first day of the week, very early in the morning, they, and certain other women with them, came to the tomb bringing the spices which they had prepared.”

If the day following the “Sabbath” mentioned in Luke 23:56 was the first day of the week, and the day before that was the Sabbath kept “according to the commandment,” this rest day had to be the seventh day of the week as the Law states in Exodus 20:8-11. It could also be a high day during the days of Unleavened Bread, and indeed mostly likely was the first day of that spring festival (Leviticus 23:7). Whatever the case, the scenario of these days is as shown at the bottom of the previous page.

There is no place for a day or more between the crucifixion and the laying of Jesus’ body in the tomb, and the Sabbath that followed … nor is there a gap mentioned in Luke 23 and 24 between that seventh day and the first day of the week. These three days constitute the time period that prophecy and Jesus Christ referred to many times as “the third day”: part of the sixth day, the entire seventh day, and part of the first day of the week. There is no record of exactly when Jesus was raised, only that “he rose again the third day according to the scriptures” (I Corinthians 15:4).

Do not forget the plain statement in Mark 16:9, “Now when He rose early on the first day of the week …,” which makes it plain that He did not rise from the grave on the Sabbath day, which is the seventh day of the week. This first day of the week begins after sundown when the Sabbath day has ended.

Following these facts there are other irrefutable truths in Luke 24 that will be covered in the next section which reveal that this first day of the week was indeed the “third day” of the three days prophesied for the crucifixion and resurrection of our Savior, Jesus Christ.

On the Road to Emmaus

When the first day of the week (Sunday) had arrived following the crucifixion and resurrection, two of the disciples were walking to a village named Emmaus, a few miles from Jerusalem. Let the text in Luke 24:13-21 describe this episode.

“That very day two of them were going to a village named Emmaus, about seven miles from Jerusalem, and they were talking with each other about all these things that had happened. While they were talking and discussing together, Jesus Himself drew near and went with them. But their eyes were kept from recognizing Him. And He said to them, ‘What is this conversation that you are holding with each other as you walk?’ And they stood still, looking sad. Then one of them, named Cleopas, answered Him, ‘Are you the only visitor to Jerusalem who does not know the things that have happened there in these days?’ And He said to them, ‘What things?’ And they said to Him, ‘Concerning Jesus of Nazareth, a man who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, and how our chief priests and rulers delivered Him up to be condemned to death, and crucified Him. But we had hoped that He was the one to redeem Israel. Yes, and besides all this, it is now the third day since these things happened.”

This seven-mile trek to Emmaus was taking place on the first day of the week, a Sunday (Luke 24:1, 12), and it was the “third day since these things happened” (verse 21). Obviously, when saying “these things” Cleopas and his friend were referring to the day on which the trial, condemnation, crucifixion, and death and burial of Jesus had occurred. That being said, then it is obvious that “these things” occurred three days before, on the previous Friday, as we recall that for the Hebrews a part of a day counted as a whole day. See the diagram on page 9 to make this clear.

This scenario reveals that Jesus was crucified on the first day of Unleavened Bread, which was an annual High Day. Some think that a crucifixion on an annual High Day was not possible. In fact, the chief priests and the elders conspired to kill Him a few days before the Feast, and they said, “Not during the feast, lest there be an uproar among the people” (Matthew 26:3-5; see also Mark 14:1-2 and Luke 22:1-2). It is apparent that the hierarchy of the Jewish religious order did not get its wish, for Jesus did end up being crucified on the first day of Unleavened Bread that year. Would Jewish laws permit such a thing?

Yes they would. According to Joachim Jeremias in The Eucharistic Words of Jesus, (SCM Press, London, England, 1966, page 781), the annual Holy Days had a separate set of rules that were less stringent than for the weekly Sabbath. For instance, on an annual Holy Day a person could be buried, but a grave could not be dug; we know that Jesus was placed in a grave already hewn out. Of course, that body had to be buried the same day as the death (Deuteronomy 21:22-23).

Jeremias also gives several historical references showing that people could be executed on an annual Holy Day. In fact, in serious cases, like being considered a false prophet — as Jesus was considered — they “… are not to be executed at once but are to be brought to the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem and kept in prison until the feast, and the sentence carried out at the Feast” (Jeremias, page 281). Thus, both the Jewish leaders and the Romans had reasons to kill the Son of God … the Jews because He threatened their monopoly on religious power and control over the people (Mark 15:10), and the Romans because He posed a potential threat to their authority since they were told by the Pharisees that He claimed to be a king. The authorities of the day had no qualms about making an example of a nonconformist like Jesus by crucifying Him when a maximum number of people could observe the event, as during a festival day in Jerusalem where all the males were commanded to gather (Deuteronomy 16:16)

3. Jesus Did Not Have to Be Crucified At the Same Time As the

Passover Lambs Were Killed.

Conclusive evidence has already been shown that Jesus was killed on Nisan 15, the first day of Unleavened Bread, but aside from that there is no requirement that He had to be crucified when the lambs were on Nisan 14. True, Paul stated,

“Cleanse out the old leaven that you may be a new lump, as you really are unleavened. For Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed” (I Corinthians 5:7).

Indeed, our Savior is our Passover lamb who gave His life so that we might have eternal life through His shed blood — which atones for our sins — but does that statement imply He had to be killed at the same time as were the Passover lambs on Nisan 14? An unpublished paper by John Sash has outlined the major defining aspects of Jesus’ death on the stake. Sash’s claim is that “It is the other sacrificial offerings, and not the Passover lamb, that symbolize the death of Christ! All of these other sacrifices were given on the 15th, the day after the Passover lamb was killed. Therefore, for Christ to fulfill these sacrifices He had to die on the same day, the 15th. This means the Last Supper was the Passover at the end of the 14th” (John Sash, Was the “Last Supper” the Passover? Did Christ Have to Die At the Same Time the Passover Lamb Was Sacrificed?, page 2).

There are ten defining aspects of Christ’s death on the stake, as Sash made clear.

(1) Christ’s death covers all men, This was not true of the Passover sacrifice, which covered only the firstborn, but the other sacrifices covered everyone, including the stranger.

(a) The Passover lamb covered only the firstborn (Exodus 11:5; 12:29).

(b) The other sacrifices (symbolizing Christ) covered all men (Exodus 12:49; Leviticus 4:13-15; Numbers 15:29; John 3:16; 11:52; Romans 3:23; 4:8; I Corinthians 15;22; II Corinthians 5:15, 19).

(2) Christ’s death redeems us from death.

(a) The Passover lamb did not redeem men from death, but only caused the death angel to pass over the firstborn of Israel; they had to be redeemed later (Exodus 13:15; Numbers 3:41, 46-47).

(b) The other sacrifices (symbolizing Christ) pictured our redemption in Christ (II Samuel 7:23-24; Psalms 49:8-9; I Corinthians 15:22; Hebrews 9:9-15; 10:14).

(3) Christ’s death pays for our sins.

(a) The Passover lamb did not pay for any sins, but notified the death angel to pass over the Israelite firstborn; it did not redeem them or cover the non-firstborn.

(b) The other sacrifices (symbolizing Christ), pictured the forgiveness of sins (Leviticus 4:35; 5:13; Numbers 15:25-26; Isaiah 53:12; Luke 24:47; I Corinthians 15:3; Galatians 1:4; Colossians 1:14; Hebrews 5:1; 7:27; 8:4-5; 9:7, 24-28; 10:12).

(4) Christ’s death was a holy offering to God.

(a) The Passover lamb is not an offering! There were no evening sacrifices established yet, nor was there a temple. It is not mentioned in the first seven chapters of Leviticus that describe all of the offerings to God. The Passover lamb was never brought to the tabernacle to be offered to God, nor was it offered as a burnt offering, a sin offering, a trespass offering, a peace offering, or a grain offering. No part was given to the priest, or heaved up or waved before God, nor did the priest kill it before God. Rather, the Israelites killed it themselves at their homes and ate it themselves.

(b) All of the other sacrifices (symbolizing Christ) are described as offerings to God. They were brought to the tabernacle before the priest, killed by him, and depending on the type were burnt totally, eaten by the priests, heave offered to God, eaten by the offerer, or waved before God (Leviticus 1:2-3; 7:37-38; Ephesians 5:2; Hebrews 7:27; 8:3; 9:9, 14, 28).

(5) The blood of Christ’s suffering sanctifies us and cleanses us from sin.

(a) The blood of the Passover lamb did not sanctify or forgive anyone. It was not sprinkled on the altar or upon the person who offered it, but was wiped on the lintel and doorposts of the Israelites’ homes to notify the death angel to pass on over. Neither did the blood redeem the firstborn because they were later redeemed with money and by the substitution of the Levites. The blood was merely a sign.

(b) The blood of the sacrifices (symbolizing Christ’s blood) did sanctify, and was holy. (Exodus 24:8; 30:10; Leviticus 1:5; Numbers 18:7; Isaiah 52:14-15; Matthew 26:28; Hebrews 9:12-14; 10:4-7; I Peter 1:18-19).

(6) Christ died outside the gates of Jerusalem.

(a) The Passover lamb was killed and consumed in the Israelites’ homes (Exodus 12:3, 10).

(b) The burnt offerings for the sins of the priests and people were taken outside the camp (Leviticus 4:11-12; Hebrews 13:11-13).

(7) The victory over Satan, the payment for sins, and the tearing of the veil to give us access to God were achieved the moment Jesus died.

(a) The Passover lamb gave no deliverance at the moment it was killed. Israel’s deliverance began when the death angel passed through Egypt that night, and deliverance did not occur until the following day (Exodus 12:6, 29, 33, 37, 51; Numbers 33:3).

(b) The sacrificial offerings picture the deliverance from sins and the forgiveness of sins, as well as the reconciliation with the Father, which occurs symbolically when the animals are sacrificed (Matthew 15:37-38; Romans 5:8-10; I Corinthians 15:56-57; Hebrews 10:19-20).

(8) Christ’s sacrificial death occurred with great suffering.

(a) The Passover lamb was killed without suffering, and then eaten.

(b) The other sacrifices picture Christ’s great suffering while being killed, such as the skinning of the burnt offering, cutting it up, burning it on the altar, beating the grain into fine flour, and so forth.

(9) Christ’s suffering and death occurred in one day.

(a) The Passover lamb was killed on one day, but was eaten the night of the next day, Nisan 15, and the remainder was burned.

(b) The other sacrifices (symbolizing Christ) were killed, and then either burned or eaten the same day. The exception was the peace offering, which could be eaten the second day, but any remaining part was burned the third day. Recall that Jesus was resurrected for our “peace” on the third day.

(10) Christ’s offering was a total offering.

(a) The Passover lamb was not an offering to God, and it was not a total sacrifice since not all of it was burned.

(b) The other sacrifices (symbolizing Christ) — the burnt and sin offerings for the priests, individuals, and congregation — were totally burned.

Jesus Christ is indeed our Passover, but the time of the killing of the lambs on the evening of the fourteenth of Nisan does not require that His death occur at that same time. Rather, the other sacrifices during the Feast of Unleavened Bread actually portray His crucifixion, His spilled blood, and His atonement for our sins. Death symbolically passes over us through the atoning blood of the Lamb of God, when we have the spirit of God within us, and we leave Egypt with a high hand to ultimately crush the evil enemy in the Red Sea and journey to the Promised Land.

4. “That Sabbath Was a High Day” (John 19:31)

It is not uncommon for people to be confused over the statement in John 19:31, which says, “… that the bodies should not remain upon the stake on the Sabbath day (for that Sabbath day was a high day) ….” Remember that this was the Preparation Day for the weekly Sabbath, as has already been shown to be the case.

The Greek word for high is megas, which means “big (literally or figuratively), in very wide applications; exceedingly, great),” indicating that this day after the crucifixion (Nisan 15, the first day of Unleavened Bread) was of special significance. This Nisan 16 megas day was, according to Pharisaical tradition in Jesus’ day, the Wave Sheaf Offering Day … a major observance in God’s Holy Day progression, and tied intimately to the Passover.

The Pharisees observed this day the day after the first day of Unleavened Bread, whereas the Sadducees observed it the day after the weekly Sabbath — on what we term Sunday — within the Days of Unleavened Bread. (Anonymous, Feast of Pentecost, The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, Volume 3, Inter-Varsity Press, Sydney, Australia, 1980, page 1188; the Mishna, Menahot 10.3; Louis Finkelstein, The Pharisees, the Sociological Background of their Faith, Volume 1, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia, 1938).

John 19:31 is obviously referring to the Pharisees’ reckoning of the Wave Sheaf Offering Day, which in the year Christ was crucified occurred on the weekly Sabbath, the day after Christ was crucified. The Sadducees, the priestly party, would be correctly keeping the Wavesheaf Day a day later, as the Torah requires.

He shall wave the sheaf before the Lord, to be accepted on your behalf; on the day after the Sabbath the priest shall wave it” (Leviticus 23:11).

5. The “Night to Be Much Observed” Is the Passover.

Some groups of believers have chosen to observe a separate event a day after the “pre-Passover”. This event is held the evening of the 14th of Nisan going into the 15th, and is described in Exodus 12:42. It is couched within the directions given to the Hebrews to keep the Passover and come out of Egypt

“It is a night to be much observed unto the Lord for bringing them out from the land of Egypt: this is that night of the Lord to be observed of all the children of Israel in their generations” (KJV).

Other translations use other words for “much observed,” such as “night of watching” (ESV) or “night of solemn observance” (NKJV). It is obvious from the context that this verse is speaking of the night of the Passover, when the Israelites ate the roasted lamb, unleavened bread, and bitter herbs with their belts fastened, their sandals on their feet, and a staff in their hands (Exodus 12:8-11). It was to be eaten in haste (verse 11), for the death angel was to pass through the land of Egypt and kill all of the firstborn of the Egyptians, and then the Israelites were to quickly gather their clans and move out towards the Red Sea … at the end of 430 years (Exodus 12: 40-41). Indeed that Passover was a “solemn observance” and a “night of watching” as they prepared to leave the nation that had held them captive for so many generations.

Traditions begun by organizations of men usually die hard, but die they must when they contradict the word of God. We must keep the Passover in the way and at the time our heavenly Father desires, not as men may erroneously instruct.

6. The Disagreement Between John 19:14 and Mark 15:25 — a Solution

One issue that has not yet been resolved while completing this Passover scenario is the apparent contradiction between John 19:14 and Mark 15:25. In Mark it says that Jesus was crucified at the third hour, about 9 a.m., while John says Jesus was at his final trial before Pilate at “about (ὡς)” the sixth hour (John 19:14). If John was using the same time reckoning system as Mark, Jesus was not yet on the stake until around noon that day. How can this difference be reconciled?

An excellent paper by James Davis entitled “The time of Jesus’ death and inerrancy: Is harmonization plausible?” (www.bible/org) addresses this problem, and postulates four possible reasons for the difference in timing of the two scriptures.

1) John 19:14 had an original reading of “the third hour” which was confused for the sixth hour. This was due to the great similarity between the Greek characters used to designate the numbers 3 (gamma, Γ) and 6 (digamma, F) . A copyist could easily have made an error in copying, and this could have been transmitted to subsequent copies on down through the centuries. According to Eusebius, “Mark says Christ was crucified at the third hour. John says that it was at the sixth hour that Pilate took his seat on the tribunal and tried Jesus. This discrepancy is a clerical error of an earlier copyist. Gamma (Γ) signifying the third hour is very close to the episemon (ς) denoting the sixth. As Matthew, Mark, and Luke agree that the darkness occurred from the sixth hour to the ninth, it is clear that Jesus, Lord and God, was crucified before the sixth hour., i.e., about the third hour, as Mark has recorded. John similarly signified that it was the third hour, but the copiest turned the gamma (Γ) into the episemon (ς).”

2) John is using a Roman civil reckoning that started the day at midnight. That would place the 6th hour at around 6 a.m., allowing for the judgement of Pilate to concur with the other gospels.

3) Mark’s reference to the crucifixion is a general statement that included some event(s) that led up to the lifting of Jesus on the stake.

4) Time approximation allows for adequate harmonization of Mark and John.

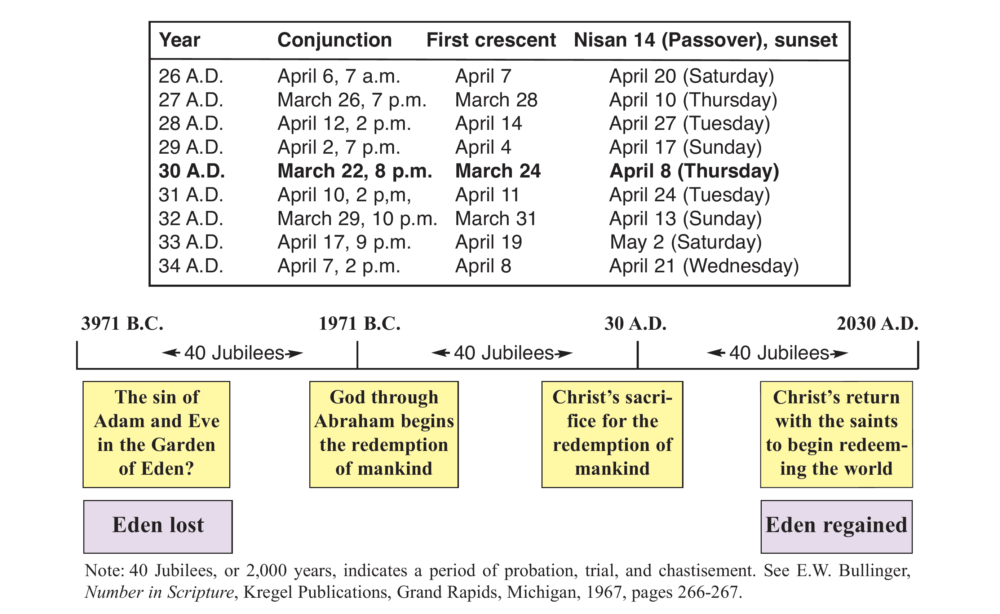

The Likely Year of the Crucifixion

Perhaps it is being presumptuous to suggest the year of Jesus’ crucifixion, but I will present this possibility: 30 A.D. The evidence is fairly straightforward when looking at the first visible crescents for the eligible years of the crucifixion. Above is a table of the first visible crescents for the years 26 to 34 A.D., as obtained from the U.S. Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications Department (see www.usno.navy.mil/ USNO/astronomical-applications/data-services/spring-phenom).

The Thursday Passover date for 30 A.D. is corroborated by F.N. Jones (The Chronology of the Old Testament, Floyd Jones Ministries, Inc., Master Books, Green Forest, Arkansas, 1993, pages 273-274), using a calendar conversion computer program designed by the Harvard Center for Astrophysics. The ephemeris generator for this software was developed from Jean Meeus’ Astronomical Formulae for Calculators, a standard formula used by astronomers today. Jones states, “Nisan 14 converts to Thursday, April 4th Gregorian calendar (6 April Julian) ….”

This date of 30 A.D. correlates well with the historical date for Jesus’ birth, in the spring of 4 B.C. I will not include evidence here to verify that date, but will note that Archbishop Ussher’s chronology of mankind’s history, which begins with Adam and Eve’s creation in 4004 B.C., gives a perfect 4,000 years (80 Jubilee cycles) from man’s creation (the First Adam) to Jesus Christ’s birth (the Second Adam).

Jesus’ ministry began at about age 30 (Luke 3:23), and lasted for about three years. If he died on the first day of Unleavened Bread in 30 A.D. (April 4), then 40 Jubilee cycles later would bring us to 2030 A.D. (See the figure below.) Is it possible that this will be the day of the return of Jesus Christ to establish the Kingdom? This means that the Tribulation could possibly begin in about April of 2023, and the Great Tribulation in the fall of 2026. These dates are not far off. Look up, and be wise! (Daniel 12:10; Luke 21:28).

There is a possibility that Christ’s ministry was only a bit over a year in length — 70 weeks — as proposed by Michael Rood in The Chronological Gospels, the Life and Seventy Week Ministry of the Messiah (Aviv Moon Publishing, Fort Mill, South Carolina, 2013). This proposal is based on the knowledge that Eusebius disbanded the “about one year” common knowledge of the length of Christ’s ministry held by theologians before Eusebius introduced the 3.5 year period in the Fourth Century B.C. Rood contends that the 3.5 year ministry is an mathematical impossibility, proven by the fact that the synchronizing marker of the feeding of the five thousand, found in all four gospels, occurred 18 days before the Feast of Tabernacles. Yet, John 6:4 states, “And the passover, a feast of the Jews, was nigh.” This was a later addition to the Scriptures, which was added by Eusebius to subvert the correct calculation of the scenario of Christ’s ministry, and His birth and crucifixion dates.

How to Observe the Passover

It is essential that God’s people observe the Passover each year, for it is a commanded observance for all of us (Exodus 12:14; Leviticus 23:14), a renewal, as it were, of our covenant to be God’s people. We must be mentally prepared for this event by examining ourselves to see if we are truly abiding by the terms of that covenant: to be keeping His laws, commandments, statutes, and judgments, even as our forefather Abraham did (Genesis 26:5; II Corinthians 13:5). Our attitude in entering into this most critical observance must be one of humility and love toward our Father in heaven, and to our Elder Brother who gave His sinless life for the lives of all sinners, as well as to our brethren within the body of Christ.

We should strive to keep the Passover the way that Jesus and the disciples did, for His example sets the stage for all aspects of our living (I John 2:4-6; I Peter 2:21). Let us emulate His example as He showed us in much detail in the four Gospels. He followed the same example as the Israelites had observed for hundreds of years since leaving Egypt, but added the symbols of His body and blood, as well as footwashing to symbolize the humility we need to be a true king and priest in the eyes of our Creator.

Below is one variation that my wife and I, and those with whom we have kept the Passover over the years, have found most acceptable. We like to read the word of God during the Passover evening, and share that reading with those who are gathered. Surely there are other variations that God would find well pleasing.

Who should partake of the Passover activities? Let us examine the Passover observance in ancient Israel, as well as at Jesus’ final Passover.

Ancient Israel (Exodus 12). Once the families of the Israelites had prepared their lambs, vegetables, and drinks, it is hard to conceive that anyone in those families were denied participation in the events. Parents and children, young and old all participated, for it was a family affair.

Christ’s last Passover (all four Gospels). Presumably there were just Jesus and the twelve apostles partaking of the Passover meal, along with the bread and wine symbols, plus the footwashing.

Does that mean that only baptized people should participate in the meal, and especially take the bread and the wine? Let’s be clear about one major issue here: The disciples did not yet have the spirit of God within them. That was given later when Jesus breathed on them after the resurrection (John 20:22-23)! This fact strongly suggests that a person does not have to be a baptized member of the body of Christ to take the symbols of the bread and wine, and participate in the meal as well; the same case can be made for footwashing, an act of service that even a child can comprehend.

If a person understands the need to serve God, and accept His body and blood as a sacrifice for sin, that person should surely be allowed to take part in the entire Passover event. God will grant His spirit to people of that mind in His own time, just as He did for the disciples who partook of the meal, the bread, the wine, and the footwashing before Christ’s crucifixion and the granting of His spirit to them.

1. Select a suitable place for a small gathering. In the case of Jesus’ last Passover, that included Himself and twelve others. There could have been others, but we do not have a record of such. The place was private and well-furnished, such as are many homes today (Matthew 26:17-19; Mark 14:12-16; Luke 22:7-13).

2. Prepare a meal, which could include meat (lamb, beef, chicken, or others) and vegetables, plus unleavened bread. Bitter herbs such as radishes, horseradish, endive, or arugula could be included to simulate the bitter world of sin in which we live, just as the bitter herbs represented the horrible life of slavery the Israelites had to endure in Egypt. Wine, tea, water, and juices can be served.

3. Gather around sundown at the end of Nisan 14 with other brethren and their families and enjoy fellowship and conversation that befits the joyous and exciting but serious tone of the Passover evening. Bring a basin for water for footwashing, and a towel to dry the feet.

4. Begin by reading some introductory scriptures such as in Matthew 26:17-25, Luke 22:7-16, John 13:31-35, and John 14 and 15.

5. Enjoy the meal together, and towards the end of the meal pause for a bit and partake of the symbols of the bread and wine. Be sure everyone has a glass of wine; a common glass might be used if desired, for this is what Christ and the disciples used. Have a small plate of several unbroken unleavened bread pieces.

The bread. Read Matthew 26:26, Mark 14:23, or Luke 22:19. Then pray over the bread, break it (to symbolize Christ’s beaten body), and pass it around the table.

The wine: Read Matthew 26:27-29, Mark 14:23-25, or Luke 22:17-18, pray over the wine (to symbolize Christ’s shed blood), and have everyone drink of his wine.

6. After the meal have a foot-washing ceremony. You can read John 13:1-20, and then assemble in a room and pair off, with one’s own mate or with someone of the same gender, and have chairs enough for everyone. Prepare basins of lukewarm water, and wash one another’s feet. Dry the feet with a towel, and perhaps rub in some essential oils, like myrrh, mint, lavender, or any other essential oil.

8. End with a hymn appropriate for the occasion (Mark 14:26).

The observance of the Passover can extend well into the night. Recall that the Israelites partook of their meal and waited until the death angel struck around midnight. Likewise, Jesus and the disciples were in the garden until midnight when Judas and the band of priests and soldiers arrived. Keeping the Passover this way will bring you very close to God and fulfill His desire for you to keep it.

Appendix I: Did the Lord Institute His “Supper” on the Paschal Night?

[From Alfred Edersheim, The Temple, Its Ministry and Services, Hendrickson Publishers, Inc., Peabody, Massachusetts, 1994, pages 311-318; published first in London, England, in 1874.]

The question, whether or not the Saviour instituted His Supper during the meal of the Paschal night, although not strictly belonging to the subject treated in this volume, is too important, and too nearly connected with it, to be cursorily passed over. The balance of learned opinion, especially in England, has of late inclined against this view. The point has been so often and so learnedly discussed, that I do not presume proposing to myself more than the task of explaining my reasons for the belief that the Lord instituted His “Supper” on the very night of the Paschal Feast, and that consequently His crucifixion took place on the first day of Unleavened Bread, the 15th of Nisan.

From the writers on the other side, it may here by convenient to select Dr. Farrar, as alike the latest and one of the ablest expositors of the contrary position. His arguments are stated in a special Excursus,(1) appended to his Life of Christ.(2) At the outset it is admitted on both sides, “that our Lord was crucified on Friday and rose on Sunday,” and, further, that our Lord could not have held a sort of anticipatory Paschal Supper in advance of all the other Jews, a Paschal Supper being only possible on the evening of the 14th of Nisan, with which, according to Jewish reckoning, the 15th began. Hence it follows, that the Last Supper which Christ celebrated with his disciples must have either been the Paschal Feast, or an ordinary supper, at which He afterwards instituted His own special ordinance.(3) Now, the conclusions at which Dr. Farrar arrives are thus summed up by him.(4) “That Jesus ate His last supper with the disciples on the evening of Thursday, Nisan 13, i.e. at the time when according to Jewish reckoning, the 14th of Nisan began; that this supper was not, and was not intended to be, the actual Paschal meal, which neither was nor could be legally eaten till the following evening; but by a perfectly natural identification, and one which would have been regarded as unimportant, the Last Supper, which was a quasi-Passover, a new and Christian Passover, and one in which, as in its antitype, memories of joy and sorrow were strangely blended, got to be identified, even in the memory of the Synoptists, with the Jewish Passover, and that St. John silently but deliberately corrected this erroneous impression, which, even in his time, had come to be generally prevalent.”

Before entering into the discussion, I must confess myself unable to agree with the a priori reasoning by which Dr. Farrar accounts for the supposed mistake of the Synoptists. Passing over the expression, that “the Last Supper was a quasi-Passover,” which does not convey to me a sufficiently definite meaning, I should rather have expected that, in order to realize the obvious “antitype,” the tendency of the Synoptists would have been to place the death of Christ on the evening of the 14th Nisan, when the Paschal lamb was actually slain, rather than on the 15th Nisan, twenty four hours after that sacrifice had taken place. In other words, the typical predilections of the Synoptists would, I imagine, have led them to identify the death of Christ with the slaying of the lamb; and it seems a priori, difficult to believe that, if Christ really died at that time, and His last supper was on the previous evening — that of the 13th Nisan, — they should have fallen into the mistake of identifying that supper, not with His death, but with the Paschal meal. I repeat: a priori, if error there was, I should have rather expected it in the opposite direction. Indeed, the main dogmatic strength of the argument on the other side lies in the consideration that the anti-type (Christ) should have died at the same time as the type (the Paschal lamb). Dr. Farrar himself feels the force of this, and one of his strongest arguments against the view that the Last Supper took place at the Paschal meal is: “The sense of inherent and symbolical fitness in the dispensation which ordained that Christ should be slain on the day and at the hour appointed for the sacrifice of the Paschal lamb.” Of all persons, would not the Synoptists have been alive to this consideration? And, if so, is it likely that they would have fallen into the mistake with which they are charged? Would not all their tendencies have lain in the opposite direction?

But to pass to the argument itself. For the sake of clearness it will here be convenient to treat the question under three aspects: — How does the supposition that the Last Supper did not take place on the Paschal night agree with the general bearing of the whole history? What, fairly speaking, is the inference from the Synoptical Gospels? Lastly, does the account of St. John, in this matter, contradict those of the Synoptists, or is it harmonious indeed with theirs, but incomplete?

How does the supposition that the Last Supper did not take place on the Paschal night agree with the general bearing of the whole history?

1. The language of the first three evangelists, taken in its natural sense, seems clearly irreconcilable with this view. Even Dr. Farrar admits: “If we construe the language of the evangelists in its plain, straightforward, simple sense, and without reference to any preconceived theories, or supposed necessities for harmonizing the different narratives, we should be led to conclude from the Synoptists that the Last Supper was the ordinary Paschal meal.” On this point further remarks will be made in the sequel.

2. The account of the meal as given, not only by the Synoptists but also by St. John, so far as he describes it, seems to me utterly inconsistent with the idea of an ordinary supper. It is not merely one trait or another which here influences us, but the general impression produced by the whole. The preparations for the meal: the allusions to it: in short, so to speak, the whole mise en scene is not that of a common supper. Only the necessities of a preconceived theory would lead one to such a conclusion On the other hand, all is just what might have been expected, if the evangelists had meant to describe the Paschal meal.

3. Though I do not regard such considerations as decisive, there are, to my mind, difficulties in the way of adopting the view that Jesus died while the Paschal lamb was being slain, far greater than those which can attach to the other theory. On the supposition of Dr. Farrar, the crucifixion took place on the 14th Nisan, “between the evenings” of which the Paschal lamb was slain. Being a Friday, the ordinary evening service would have commenced at 12:30 p.m.,(5) and the evening sacrifice offered. say, at 1:30, after which the services connected with the Paschal lamb would immediately begin. Now it seems to me almost inconceivable, that under such circumstances, and on so busy an after-noon,(6) there should have been, at the time when they must have been most engaged, around the cross that multitude of reviling Jews, “likewise also the chief priests, mocking him, with the scribes,” which all the four evangelists record (Matt. 27:39, 41; Mark 15:29, 31; Luke 23:35; John 19:20). Even more difficult does it seem to me to believe, that after the Paschal lamb had been slain, and while the preparations for the Paschal Supper were going on, as St. John reports (John 20:38, 39), an “ honourable councilor,” like Joseph of Arimathea, and a Sanhedrist, like Nicodemus, should have gone to beg of Pilate the body of Jesus, or been able to busy themselves with His burial.

I proceed now to the second question: What, fairly speaking, is the inference from the Synoptical Gospels?

1. To this, I should say, there can be only one reply: — The Synoptical Gospels, undoubtedly, place the Last Supper in the Paschal night. A bare quotation of their statements will establish this: — “Ye know that after two days is the Passover” (Matt. 26:2), “Now the first day of unleavened bread the disciples came to Jesus, saying unto Him, Where wilt Thou that we prepare for Thee to eat the Passover?” (Matt. 26:17 “I will keep the Passover at thy house” (Matt. 26:18): “They made ready the Passover”: (Matt. 26:19. Similarly, in the Gospel by St. Mark (Mark 14:12-17): “And the first day of unleavened bread, when they killed the Passover, the disciples said to Him, Where wilt Thou that we go and prepare, that Thou mayest eat the Passover?” “The Master saith, Where is the guest-chamber, where I shall eat the Passover with my disciples?” “There make ready for us.” “And they made ready the Passover. And in the evening He cometh with the twelve. and as they sat and did eat …” And in the Gospel by St. Luke (Luke 22:7-15): “Then came the day of unleavened bread, when the Passover must be killed;” “Go and prepare us the Passover, that we may eat,” “Where is the guest-chamber where I shall eat the Passover with my disciples? There make ready;” “And they made ready the Passover.” “And when the hour was come He sat down;” “With desire have I desired to eat this Passover with you BEFORE I SUFFER.” It is not easy to understand how even a “preconceived theory” could weaken the obvious import of such expressions, especially when taken in connection with the description of the meal that follows.

2. Assuming, then, the testimony of the Synoptical Gospels to be unequivocally in our favour, it appears to me extremely improbable that, in such a matter, they should have been mistaken, or that such an “erroneous impression” could — and this even “in the time of St. John” — have “come to be generally prevalent.” On the contrary, I have shown that if mistake there was, it would most likely have been rather in the opposite direction.

3. We have now to consider what Dr. Farrar calls “the incidental notices preserved in the Synoptists,” which seem to militate against their general statement. Selecting those which are of greatest force, we have: —

(a) The fact “that the disciples (John 13:22) suppose Judas to have left the room in order to buy what things they had need of against the feast.” But the disciples only suppose this; and in the confusion and excitement of the scene such a mistake was not unintelligible. Besides, though servile work was forbidden on the first Paschal day, the preparation of all needful provision for the feast was allowed, and must have been the more necessary, as, on our supposition, it is followed by a Sabbath. Indeed, the Talmudical law distinctly allowed the continuance of such preparation of provisions as had been commenced on the “preparation day” (Arnheim, Gebetb. d. Isr., p. 500, note 69. a). In general, we here refer to our remarks at p. 195 only adding, that even now Rabbinical ingenuity can find many a way of evading the rigour of the Sabbath-law.

(b) As for the meeting of the Sanhedrim, and the violent arrest of Christ on such a night of peculiar solemnity, the fanatical hatred of the chief priests, and the supposed necessities of the case, would sufficiently account for them. On any supposition we have to admit the operation of these causes, since the Sanhedrim confessedly violated, in the trial of Jesus, every principle and form of their own criminal jurisprudence.

Lastly, we have to inquire: Does the account of St. John contradict those of the Synoptists, or is it harmonious, indeed, with them, but incomplete?

1. Probably few would commit themselves to the statement, that the account of St. John necessarily contradicts those of the Synoptists. But the following are the principal reasons urged by Dr. Farrar for the inference that, according to St. John, the Last Supper took place the evening before the Paschal night: —

(a) Judas goes, as is supposed, to buy the things that they have need of against the feast. This has already been explained.

(b) The Pharisees “Went not into the judgment-hall, lest they should be defiled, but that they might eat the Passover.” And in answer to the common explanation that “the Passover” here means the 15th day, Chagigah, (7) he adds, in a foot-note, that “there was nothing specifically Paschal” about this Chagigah. Dr. Farrar should have paused before committing himself to such a statement. One of the most learned Jewish writers, Dr. Saalschutz, is not of his opinion. He writes as follows:(8) “The whole feast and all its festive meals were designated as the Passover.” See Deut. 16:2, compare 2 Chron. 30:24 and 35:8, 9; Sebach. 99, b, Rosh ha Sh. 5, a, where it is expressly said, “What is the meaning of the term Passover?” (Answer) “The peace-offerings of the Passover.;” Illustrative Rabbinical passages are also quoted by Lightfoot (9) and by Schottgen. (10) As a rule of Chagigah was always brought on the 14th Nisan, and it required Levitical purity. Lastly Dr. Farrar himself admits that the statement of St. John (John 18:28) must not be too closely pressed, “for that some Jews must have even gone into the judgment-hall without noticing ‘the defilement’ is clear.”

(c) According to St. John (John 19:31), the following Sabbath was “a high day,” or “a great day,” on which Dr. Farrar comments: “Evidently because it was at once a Sabbath, and the first day of the Paschal Feast.” Why not the second day of the feast, when the first omer was presented in the Temple? To these may be added the following among the other arguments advanced by Dr. Farrar: — (d) The various engagements recorded in the Gospels on the day of Christ’s crucifixion are incompatible with a festive day of rest, such as the 15th Nisan. The reference to “Simon the Cyrenian coming out of the country” seems to me scarcely to deserve special notice. But then Joseph of Arimathaea bought on that day the “fine linen” (Mark 14:46) for Christ’s burial, and the women “prepared spices and ointments” (Luke 23:56)11. Here, however, it should be remembered, that the rigour of the festive was not like that of the Sabbatic rest, that there were means of really buying such a cloth without doing it in express terms (an evasion known to Rabbinical law). Lastly, the Jerusalem Talmud (Ber. 5, b) expressly declares it lawful on Sabbaths and feast-days to bring a coffin, graveclothes, and even mourning flutes — in short, to attend to the offices for the dead — just as on ordinary days. This passage though, as far as I know, never before quoted in this controversy, is of the greatest importance.

(e) Dr. Farrar attaches importance to the fact that Jewish tradition fixes the death of Christ on the 14th Nisan.(12)But these Jewish traditions, to which an appeal is made, are not only of a late date, but wholly unhistorical and valueless. Indeed, as Dr. Farrar himself shows,(13) they are full of the grossest absurdities. I cannot here do better than simply quote the words of the great Jewish historian, Dr. Jost:(14) “Whatever attempts may be made to plead in favour of these Talmudic stories, and to try and discover some historical basis in them, the Rabbis of the third and fourth centuries are quite at sea about the early Christians, and deal in legends for which there is no foundation of any kind.”

(f) Dr. Farrar’s objection that “after supper” Jesus and His disciples went out, which seems to him inconsistent with the injunction of Ex. 12:22, and that in the account of the meal there is an absence of that hurry which, according to the law, should have characterized the supper, arises from not distinguishing the ordinances of the so-called “Egyptian” from those of “the permanent Passover.” On this and kindred points the reader is referred to Chaps. 11, 12.

(g) The only other argument requiring notice is that in their accounts the three Synoptists “give not the remotest hint which could show that a lamb formed the most remarkable portion of the feast.” Now, this is an objection which answers itself. For, according to Dr. Farrar, these Synoptists had, in writing their accounts, been under the mistaken impression that they were describing the Paschal Supper. As for their silence on the subject, it seems to me capable of an interpretation the opposite of that which Dr. Farrar has put upon it. Considering the purpose of all which they had in view — the fulfilment of the type of the Paschal Supper, and the substitution for it of the Lord’s Supper — their silence seems not only natural, but what might have been expected. For their object was to describe the Paschal Supper only in so far as it bore upon the institution of the Lord’s Supper. Lastly, it is a curious coincidence that throughout the whole Mishnic account of the Pascal Supper there is only one isolated reference to the lamb — a circumstance so striking, that, for example, Caspari has argued from it (15) that ordinarily this meal was what he calls “a meal of unleavened bread,” and that in the majority of cases there was no Passover-lamb at all! I state the inference drawn by Dr. Caspari, but there can scarcely be any occasion for replying to it.

On the other hand, I have now to add two arguments taken from the masterly disquisition of the whole question by Wieseler,(16) to show that St. John, like the Synoptists, places the date of the crucifixion on the 15th Nisan, and hence that of the Last Supper on the evening of the 14th.

(a) Not only the Synoptists, but St. John (John 18:39) refers to the custom of releasing a prisoner at “the feast,” or, as St. John expressly calls it, “at the Passover.” Hence the release of Barabbas, and with it the crucifixion of Jesus, could nothave taken place (as Dr. Farrar supposes) on the 14th of Nisan, the morning of which could not have been designated as “the feast,” and still less as “the Passover.”

(b) When St. John mentions (John 18:28) that the accusers of Jesus went not into Pilate’s judgment-hall “lest they should be defiled; but that they might eat the Passover,” he could not have referred to their eating the Paschal Supper. For the defilement thus incurred would only have lasted to the evening of that day, whereas the Paschal Supper was eaten after the evening had commenced, so that the defilement of Pilate’s judgment-hall in the morning would in no way have interfered with their eating the Paschal Lamb. But it would have interfered with their either offering or partaking of the Chagigah on the 15th Nisan.(17)

2. Hitherto I have chiefly endeavored to show that the account of St. John is harmonious with that of the Synoptists in reference to the time of the Last Supper. But, on the other hand, I am free to confess that, if it had stood alone, I should not have been able to draw the same clear inference from it as from the narratives of the first three gospels. My difficulty here arises, not from what St. John says, but from what he does not say. His words, indeed, are quite consistent with those of the Synoptists, but, taken alone, they would not have been sufficient to convey, at least to my mind, the same clear impression. And here I have to observe that St. John’s account must in this respect seem equally incomplete, whichever theory of the time of the Last Supper be adopted. If the Gospel of St. John stood alone, it would, I think, be equally difficult for Dr. Farrar to prove from it his, as for me to establish my view. He might reason from certain expressions, and so might I; but there are no such clear, unmistakable statements as those in which the Synoptists describe the Passover night as that of the Last Supper. And yet we should have expected most fulness and distinctness from St. John!

Is not the inference suggested that the account in the Gospel of St. John, in the form in which we at present possess it, may be incomplete? I do not here venture to construct a hypothesis, far less to offer a matured explanation, but rather to make a suggestion of what possibly may have been, and to put it as a question to scholars. But once admit the idea, and there are, if not many, yet weighty reasons, to confirm it For,

1. It would account for all the difficulties felt by those who have adopted the same view as Dr. Farrar, and explain, not, indeed, the supposed difference — for such I deny — but the incompleteness of St. John’s narrative, as compared with those of the Synoptists.

2. It explains what otherwise seems almost unaccountable. I agree with Dr. Farrar that St. John’s “accounts of the Last Supper are incomparably more full than those of the other evangelists,” and that he “was more immediately and completely identified with every act in those last trying scenes than any one of the apostles.” And yet, strange to say, on this important point St. John’s information is not only more scanty than that of the Synoptists, but so indefinite that, if alone, no certain inference could be drawn from it. The circumstance is all the more inexplicable if, as on Dr. Farrar’s theory, “the error” of the Synoptists was at the time “generally prevalent,” and “St. John silently but deliberately” had set himself to correct it.

3. Strangest of all, the Gospel of St. John is the only one which does not contain any account of the institution of the Lord’s Supper, and yet, if anywhere, we would have expected to find it here.

4. The account in John 13 begins with a circumstantiality which leads us to expect great fulness of detail. And yet, while maintaining throughout that characteristic, so far as the teaching of Jesus in that night is concerned, it almost suddenly and abruptly breaks off (about ver. 31) in the account of what He and they who sat with Him did at the Supper.

5. Of such a possible hiatus there seems, on closer examination, some internal confirmation, of which I shall here only adduce this one instance — that chapter 14 concludes by, “Arise, let us go hence;” which, however, is followed by other three chapters of precious teaching and intercessory prayer, when the narrative is abruptly resumed, by a strange repetition, as compared with 14:31, in these words (18:1): “When Jesus had spoken these words, He went forth with His disciples over the brook Cedron.”

Further discussion would lead beyond the necessary limits of the present Excursus. Those who know how bitterly the Quartodeciman controversy raged in the early Church, and what strong things were put forth by the so-called “disciples of John” in defence of their view, that the Last Supper did not take place on the Paschal night, may see grounds to account for such a hiatus. In conclusion, I would only say that, to my mind, the suggestion above made would in no way be inconsistent with the doctrine of the plenary inspiration of Holy Scripture.

Footnotes

- Excursus 10.

- Vol. 2, pp. 474-483.

- Dr. Farrar rightly shrinks from the conclusions of Caspari (Chron. Geogr. Einl. in d. Leben Jesu, p. 164, etc.), who regards it as what he calls “a Mazzoth-meal” without a Pascal lamb. The suggestion is wholly destitute of foundation.

- Life of Christ, 2, p. 482.

- See page 174.

- See the chapter on the “Paschal Rites.”

- Page 170 etc., and page 199, etc., of this vol.

- Mos. Recht, p. 414. The argument and quotations from the Talmud are also given in Relandus, antiq., p 426. For a full treatment of the question see Lightfoot, Horae Hebr. p. 1121.

- Horae Hebr. p. 1121. etc.

- Horae Hebr. p. 400.

- It should not be overlooked that these supposed inconsistencies appear in the accounts of the Synoptists, who, according to Dr. Farrar, wished to convey that Christ was crucified on the 15th Nisan. If really inconsistencies, they are very gross, and could scarcely have escaped the writers.

- I have not been able to verify Dr. Farrar’s references to Mishnah, Sanh. 6.2 and 10.4. But I agree with Gratz (Gesch. d. Juden., 3, p. 242. note), that much in Sanh. 7 bears, though unexpressed, reference to the proceedings of the Sanhedrim against Christ.

- Excursus, 2, p. 452.